THE PATTERN OF THE UPRISINGS

The uprisings in the north and south of Iraq are often labelled respectively as Kurdish and Shi'a uprisings. While the north is mostly Kurdish and the south is mostly Shi'a, the uprisings' participants included small numbers of other groups. Available data on Iraq's ethnic makeup is neither detailed nor highly reliable, especially with regard to cities like Kirkuk that are the subject of political contention. The predominantly Kurdish cities of the north are also home to minorities of Chaldean, Armenian, and Assyrian Christians, Arab Muslims, and Turkmans (Turkic Muslims). In the South can be found minorities of Christians and Sunni Muslims, particularly in Basra and its environs. Also scattered throughout Iraq at the time were workers from Egypt, Jordan, and other Arab countries.

The revolts of March 1991 followed a general pattern. On the day that a city rebelled, masses of unarmed or lightly armed civilians and small contingents of rebels converged in the streets. Shouting anti-regime slogans, they descended on government buildings, especially offices of the security forces. These were then attacked, usually with considerable bloodshed on both sides. Government forces fought back, but then were either killed or captured, or allowed to flee. Once in control, the rebels flung open the regime's prisons and interrogation centers, and seized small caches of weapons.

The outpouring of popular support for the uprising was largely spontaneous, although some long-term planning had taken place, particularly in the north. The revolt was fueled by a perception that Iraqi security forces were uniquely vulnerable at the time, and by long-smoldering anger at government repression and the devastation wrought by two wars in a decade.

When asked by MEW to describe the uprising, Kurdish refugees often began by recounting past government persecution: arbitrary arrest and torture, disappearances, eviction from the countryside, the destruction of villages, and the use of chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians in 1987 and 1988. The Shi'a of the south also spoke of arbitrary arrests, torture and disappearances, and about the expulsion of thousands of Shi'a to Iran in the early years of the Iran-Iraq war.

Once under way, the March 1991 uprising gathered momentum as soldiers either switched sides or deserted. The army, which is said to have grown from 140,000 in 1977 to around 1 million at the time of the invasion of Kuwait, contained substantial anti-government elements; Shi'a Arabs accounted for 80 percent of the fighting ranks and about 20 percent of the officers.[75] In the north, the defection of much of the government-recruited Kurdish militia, who vastly outnumbered the pesh merga, gave considerable force to the revolt. Journalists reported that their defection was the fruit of months of planning and psychological warfare by Kurdish rebel leaders.

Unlike the pesh merga, the Shi'a resistance lacked an organized fighting force, although it maintained cells and had carried out armed operations on occasion. The Shi'a opposition has long enjoyed sanctuary and support from the Iranian regime, although Teheran does not appear to have furnished significant material or logistical assistance during the March 1991 uprising.

Once the loyalist troops regrouped and mounted their counteroffensive, only massive foreign assistance or intervention could have saved the ill-equipped and inexperienced rebels. With little more than Kalashnikovs, machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, and a few captured tanks and artillery pieces, the Shi'a and Kurdish rebels were almost defenseless against helicopter gunships and indiscriminate mortar and artillery barrages. They had few anti-tank weapons and even fewer surface-to-air missiles.

The civilian toll was high throughout the country. Thousands of unarmed civilians were killed by indiscriminate fire from loyalist tanks, artillery cannons and helicopters; and later, when security forces rolled into a city and executed persons on the streets, in homes and in hospitals. The violence was heaviest in the south, where a smaller portion of the local population had fled than in Kurdish areas, owing partly to the danger of escaping through the south's flat, exposed terrain. Those who remained in the south were at the mercy of advancing government troops, who went through neighborhoods, summarily executing hundreds of young men and rounding up thousands of others.

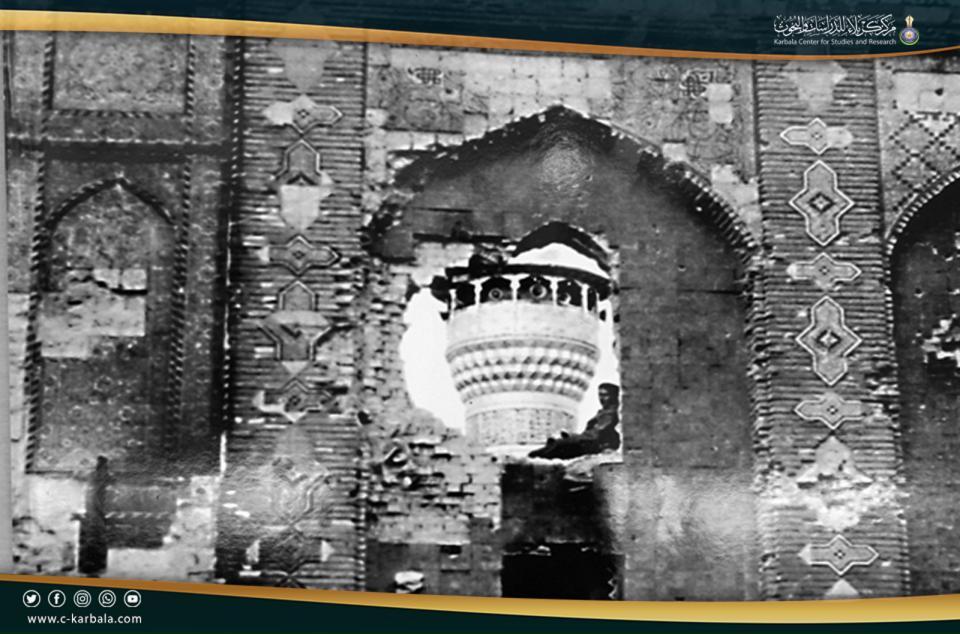

There were variations to this general pattern. Basra was the scene of chaotic, pitched battles for several days, but never fell completely into rebel hands. In other cities, the rebels ousted the security forces with little difficulty. The army later recaptured some cities, such as Karbala and al-Najaf, only after bitter fighting, but swept into others, such as Suleimaniyya, with little resistance.

Just as the experience of years of repression fed the fury of the uprising, it fueled the terrified exodus as soon as the rebellion began to falter. During March and early April, nearly two million Iraqis escaped from strife-torn cities to the mountains along the northern borders, into the southern marshes, and into Turkey and Iran. Their exodus was sudden and chaotic, with thousands fleeing on foot, on donkeys, or crammed onto open-backed trucks and tractors. In the south, many fled into or through the maze of marshes that straddle the Iranian border. Thousands, many of them children, are thought to have died or suffered injury along the way, primarily from adverse weather, unhygienic conditions and insufficient food and medical care. Some were killed by army helicopters, which deliberately strafed columns of fleeing civilians in a number of incidents in both the north and south. Others were injured when they stepped on mines planted by Iraqi troops near the eastern border during the war with Iran. The environmental organization Greenpeace has estimated that the death rate among Kurdish and Shi'a refugees and displaced persons averaged 1,000 daily during April, May and June 1991.