It is common knowledge that Frank Herbert’s classic Dune novels are chock-full of Islamic and MENA (Middle Eastern and North African) references. However, as a Muslim reader, I have long maintained that the Muslim influences go deeper than many may have realized. I am of the theory that if one is Muslim, or otherwise intimately aware of Muslim traditions, that person’s experience of Dune differs vastly from any other reader’s encounter with the saga.

According to Tor.com, the appendix traces the origins of the Orange Catholic Bible (OCB), the dominant religious text of the Dune universe, and the religion of the Fremen, the people indigenous to the eponymous planet, formally known as Arrakis. While the appendix incorporates a variety of religious and philosophical references—including to Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Navajo traditions, Roman paganism, and even Nietzsche—the thrust of the historical narrative is overwhelmingly Muslim, and perhaps specifically Shi‘i.

The appendix narrates a history in which religions respond to technological change. The advent of spaceflight and of artificial intelligence induces dramatic shifts in religious attitudes due to the mystical implications of spaceflight and the destructive effects of thinking machines. This leads to bloody wars, and people come to realize that, in seeking these technological developments, they lost touch with their shared religious commandment to “not disfigure the soul” (633). Amidst this uncertainty, industry (the Spacing Guild, which aims to control Arrakis’s valuable resource, the spice) and the Bene Gesserit (who harbor similar goals) encourage religious leaders to form the Commission of Ecumenical Translators (CET), an essentially perennialist project—in other words, one which sees every faith as an expression of the same universal truth. The Commission is founded on the principle that all religions share a belief in a “Divine Essence” and that no religion “possess[es]… the one and only revelation” (633). The result is the OCB.

What is remarkable about Bomoko’s reproach of the OCB is how it grapples with the question of religious change thousands of years into the future. It offers what, to my mind, is a thoroughly Muslim answer. The CET attempts to create a new religion in the face of massive technological change, as a way to wring order from chaos. In turn, Bomoko laments the CET’s creation of new symbols, new idols. This is comparable to most Muslims’ belief in the sanctity of revelations and the sunnah of the prophets: The Qur’an is the actual word of God as told by the angel Jibril to the Prophet Muhammad, and the Prophet is, as in the crucial Qur’anic phrase, the “Seal of the Prophets” (the “Seal” is usually understood to mean there will be no further prophets until the apocalypse). Inventing or revising revelation flies in the face of these core tenets. And that is what the CET did in producing the OCB. The sanctity of original revelation is underscored as a Muslim principle in Dune when the appendix notes that Fremen beliefs partly derive from “the Muadh Quran with its pure Ilm and Fiqh,” an allusion to Muadh Ibn Jabal, a scribe and companion of the Prophet who compiled the Qur’an during the Prophet’s lifetime. (In Islam, ‘ilm refers to knowledge in a broad sense, including both rational inquiry and experiential knowledge.)

All in all, it is a very Muslim answer (if not the only possible one) to say that reform should not involve the use of reason to modify revelation and to smooth over bespoke traditions. Indeed, Bomoko is described as an “Ulema” (from the Arabic for “scholar”) of the “Zensunnis” (a future religion that, at least by its name, syncretizes Sunni Islam and Buddhism) (637). The appendix states that he is “one of the fourteen delegates who never recanted” from their tradition when participating in the perennialist, rationalist agenda of the CET (637). Bomoko, while sympathetic to all religions, did not step into the muddy courtyard.

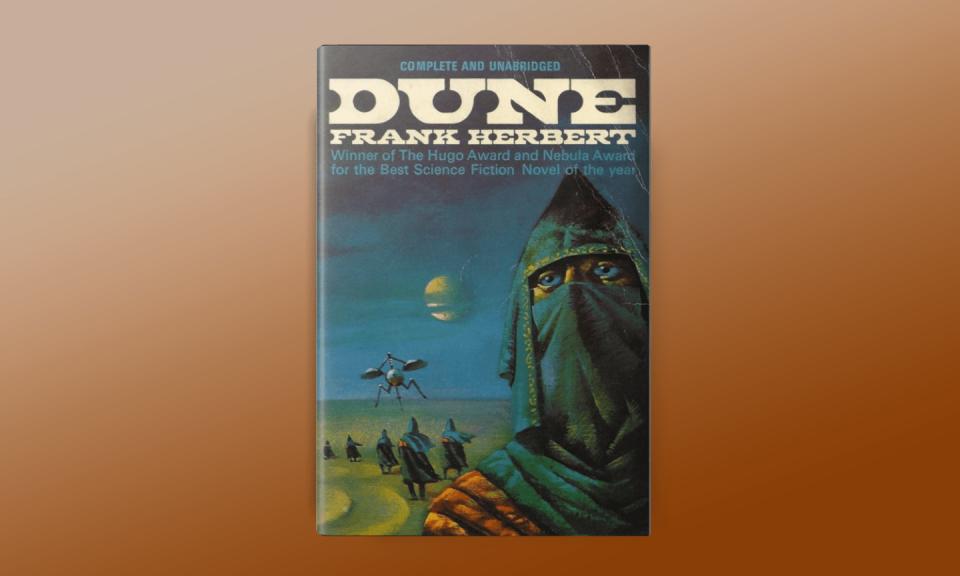

Dune is a 1965 science-fiction novel by American author Frank Herbert, originally published as two separate serials in Analog magazine. It tied with Roger Zelazny's This Immortal for the Hugo Award in 1966,[2] and it won the inaugural Nebula Award for Best Novel.[3] It is the first installment of the Dune saga; in 2003, it was cited as the world's best-selling science fiction novel.[4][5]

Perhaps most significantly, the tensions described in the appendix seem to also allude to the problem of succession to the Prophet Muhammad. While Bomoko is a Zensunni—a partial reference to Sunni Islam—he is also one of the aforementioned fourteen delegates or “Fourteen Sages” to the CET who did not recant from their tradition (637). The Fourteen Sages is likely a reference to the “Fourteen Infallibles” in Twelver Shi‘i Islam, which is alluded to in the appendix as one of the beliefs by which people reject the OCB (the aforementioned “Twelve Saints”). The Infallibles include the Prophet Muhammad, his daughter Fatimah, and the Twelve Imams who succeeded them. It is important to note that Sunni and Shi‘a labels were retrospectively ascribed to these disputes. In standard narratives, Sunnis believe that particular caliphs were to succeed the Prophet’s political leadership, beginning with his companion Abu Bakr, and that the establishment of the Umayyad Dynasty was the end of a golden period of four “righteously-guided caliphs.” Meanwhile, Twelver Shi‘as believe that succession should have gone to the Infallibles. Disputes about succession resulted in the bloody massacre of the Prophet’s family by the Umayyad Caliph Yazid I in the Battle of Karbala, regarded as a tragedy in both Sunni and Shi‘a narratives.

It is quite possible that the religious changes contemplated in the appendix, and in the Dune saga as a whole, are allegories to these ideas and historical narratives. The strict adherence to law in the OCB might be read as the rigid orthodoxy which Bomoko and the other Fourteen Sages rejected, akin to questions about succession and orthodoxy in early Muslim history. The allegory to Shi‘i narratives is particularly redolent in Bomoko’s above-quoted line (“You who have defeated us say to yourselves that Babylon is fallen and its works have been overturned.”), which may evoke the tragedy of Karbala. Certainly, Karbala was not a “Sunni-Shi‘a” conflict, as it has sometimes been retrospectively narrated, and whether or how it had to do with orthodoxy is disputed—but, if Herbert was thinking of Karbala, he may not have grasped the ahistoricity of such categories. That said, the fact that Bomoko was both a Zensunni and, apparently, one of (or an allegory to) the Twelve Imams, indicates that, whether Herbert realized it or not, the appendix concurrently challenges clean labels. Moreover, Twelver Shi‘as believe that the last of the Infallibles, the Twelfth Imam, is the Mahdi (“The Rightly Guided One”), who has already been born and will emerge during the apocalypse (Sunnis also believe in the Mahdi but believe him not yet born). Of course, Paul becomes known as the Mahdi in the course of the first novel (the Fremen translate it as “The One Who Will Lead Us Into Paradise”).

Lastly, the appendix’s description of the Bene Gesserit’s “Azhar Book” seems to contain several of these possible allegories. The description likely refers to Al-Azhar University, which was founded in Egypt in 972. The university initially taught multiple traditions within Islam, much like the Azhar Book in Dune indexes multiple religions, a “bibliographical marvel that preserves the great secrets of the most ancient faiths” (635). The reference to Al-Azhar University may be an allegory for the influence of modernization on Al-Azhar during colonization, where the above debates about taqlid and ijtihad have been a subject of much discussion among historians.